Facing Reality: The Essential Skill of Radical Acceptance in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy

Jean-Gabrielle Short • May 19, 2024

Radical Acceptance in DBT is a Distress Tolerance skill, and it stands as one of the most transformative and foundational skills available to those who are struggling with their emotions. For individuals grappling with intense emotional challenges, Radical Acceptance offers a pathway to peace and resilience. It is a skill that invites individuals to fully acknowledge and embrace their current reality, without judgment, resistance, or avoidance. This acceptance is not about approval or resignation but about seeing things as they are, which can be profoundly liberating.

Radical acceptance is the practice of completely and totally accepting something from the depths of your soul, with your heart and your mind. This practice is crucial in DBT because many of the problems faced by those with BPD are exacerbated by an inability to accept painful realities. When faced with distressing situations, the instinctual response is often to reject or fight against the reality, which can intensify emotional suffering. By accepting the reality of a situation, individuals can reduce the additional suffering caused by resistance and begin to address the actual problem.

Radical acceptance, while profoundly transformative, is undeniably challenging. It requires an immense amount of courage and inner strength to face and acknowledge painful realities without resistance or judgment. This difficulty arises from our natural inclination to reject or deny distressing situations, as well as the intense emotions that often accompany them. However, it is crucial to understand that radical acceptance does not imply approval or endorsement of the negative events or circumstances that have occurred. Instead, it is a recognition of reality as it is, which allows us to address our suffering more effectively. By accepting the truth of our experiences, we can begin to heal and move forward, rather than remaining trapped in a cycle of denial and resistance.

This concept of Radical Acceptance is complemented by the DBT skill known as "Turn the Mind." The "Turn the Mind" skill is a practical method to shift one's perspective and attitude towards acceptance. It involves a deliberate and conscious decision to accept reality as it is, which can be particularly challenging when faced with painful or uncomfortable truths. Turning the mind towards acceptance is a moment-to-moment practice, especially when the temptation to reject reality is strong.

The process of turning the mind involves several steps. First, it requires recognition of the need to accept reality. This awareness often comes with the understanding that fighting against reality only increases suffering. Next, individuals must make an inner commitment to accept the situation. This decision is often accompanied by a sense of inner peace, even if the external circumstances remain unchanged. Finally, turning the mind requires practice and persistence, as the pull towards non-acceptance can be strong, especially in moments of high emotional distress.

Radical acceptance and the "Turn the Mind" skill are particularly powerful because they address the root of emotional suffering rather than just the symptoms. When individuals can accept their reality, they are better equipped to respond to it in a balanced and effective manner. This acceptance allows for clearer thinking, more adaptive emotional responses, and healthier decision-making. In essence, radical acceptance creates a foundation upon which other DBT skills can be built and effectively utilised.

Moreover, the practice of radical acceptance fosters a sense of inner strength and resilience. It teaches individuals that they can endure difficult emotions and situations without being overwhelmed or destroyed by them. This resilience is crucial for those with BPD, who often experience intense and rapidly shifting emotions. By accepting these emotions rather than fighting against them, individuals can navigate their emotional landscape more effectively.

For those considering DBT, understanding and practicing radical acceptance can be a transformative step towards healing and growth. It is a skill that requires patience, dedication, and self-compassion. As individuals learn to turn their minds towards acceptance, they begin to break free from the cycle of suffering and move towards a life of greater peace and fulfillment.

Til next week,

Jean

Radical acceptance is the practice of completely and totally accepting something from the depths of your soul, with your heart and your mind. This practice is crucial in DBT because many of the problems faced by those with BPD are exacerbated by an inability to accept painful realities. When faced with distressing situations, the instinctual response is often to reject or fight against the reality, which can intensify emotional suffering. By accepting the reality of a situation, individuals can reduce the additional suffering caused by resistance and begin to address the actual problem.

Radical acceptance, while profoundly transformative, is undeniably challenging. It requires an immense amount of courage and inner strength to face and acknowledge painful realities without resistance or judgment. This difficulty arises from our natural inclination to reject or deny distressing situations, as well as the intense emotions that often accompany them. However, it is crucial to understand that radical acceptance does not imply approval or endorsement of the negative events or circumstances that have occurred. Instead, it is a recognition of reality as it is, which allows us to address our suffering more effectively. By accepting the truth of our experiences, we can begin to heal and move forward, rather than remaining trapped in a cycle of denial and resistance.

This concept of Radical Acceptance is complemented by the DBT skill known as "Turn the Mind." The "Turn the Mind" skill is a practical method to shift one's perspective and attitude towards acceptance. It involves a deliberate and conscious decision to accept reality as it is, which can be particularly challenging when faced with painful or uncomfortable truths. Turning the mind towards acceptance is a moment-to-moment practice, especially when the temptation to reject reality is strong.

The process of turning the mind involves several steps. First, it requires recognition of the need to accept reality. This awareness often comes with the understanding that fighting against reality only increases suffering. Next, individuals must make an inner commitment to accept the situation. This decision is often accompanied by a sense of inner peace, even if the external circumstances remain unchanged. Finally, turning the mind requires practice and persistence, as the pull towards non-acceptance can be strong, especially in moments of high emotional distress.

Radical acceptance and the "Turn the Mind" skill are particularly powerful because they address the root of emotional suffering rather than just the symptoms. When individuals can accept their reality, they are better equipped to respond to it in a balanced and effective manner. This acceptance allows for clearer thinking, more adaptive emotional responses, and healthier decision-making. In essence, radical acceptance creates a foundation upon which other DBT skills can be built and effectively utilised.

Moreover, the practice of radical acceptance fosters a sense of inner strength and resilience. It teaches individuals that they can endure difficult emotions and situations without being overwhelmed or destroyed by them. This resilience is crucial for those with BPD, who often experience intense and rapidly shifting emotions. By accepting these emotions rather than fighting against them, individuals can navigate their emotional landscape more effectively.

For those considering DBT, understanding and practicing radical acceptance can be a transformative step towards healing and growth. It is a skill that requires patience, dedication, and self-compassion. As individuals learn to turn their minds towards acceptance, they begin to break free from the cycle of suffering and move towards a life of greater peace and fulfillment.

Til next week,

Wise-Mind Matters

Emotions, the Nervous System, and Why Anger Can Feel So Intense Anger is one of the most misunderstood emotions, particularly for people who experience it intensely, quickly, or in ways that feel difficult to control. In clinical practice, anger is often labelled as a problem behaviour or a sign of poor coping, rather than understood as a meaningful emotional response shaped by biology, learning history, and current context. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy takes a very different position. Rather than asking how to eliminate anger, DBT asks why anger arises, what function it serves, and how people can learn to experience it without causing harm to themselves or others. This article explores anger through two closely connected frameworks. First, the DBT model of emotions, which explains how emotions are generated and maintained. Second, the role of the autonomic nervous system, which helps us understand why anger can escalate rapidly and feel overwhelming in the body. When these models are integrated, anger becomes less mysterious and less moralised. It becomes something that can be understood, anticipated, and worked with skillfully. The DBT Model of Emotions In DBT, emotions are not random or irrational. They arise through a predictable sequence of events. An emotion begins with a prompting event, which can be external, such as a conflict or perceived rejection, or internal, such as a thought, memory, or physical sensation. This prompting event interacts with a person’s vulnerability factors. These include things like sleep deprivation, stress, trauma history, chronic invalidation, or ongoing relational strain. When vulnerability is high, even relatively small events can trigger strong emotional responses. This is particularly relevant for anger, which is often activated in situations involving perceived threat, injustice, abandonment, or boundary violations. Once the emotion is triggered, it unfolds across multiple systems. There is an emotional experience, changes in thoughts, urges to act, and physiological arousal in the body. Anger, from a DBT perspective, often includes thoughts such as “This is not fair” or “I am being disrespected,” urges to confront, attack, withdraw, or defend, and physical sensations such as muscle tension, heat, increased heart rate, and narrowed attention. These components reinforce one another, creating momentum. If nothing interrupts the process, anger can escalate quickly and lead to behaviours that may later be regretted. Importantly, DBT emphasises that emotions themselves are not the problem. Emotions evolved to help us survive. Anger, in particular, is designed to mobilise energy, protect boundaries, and signal that something important is at stake. Problems arise when anger becomes too intense, lasts too long, or leads to behaviours that create further suffering. Emotional Vulnerability and Anger Escalation Some people are biologically more emotionally sensitive than others. DBT refers to this as emotional vulnerability, which includes heightened sensitivity to emotional cues, intense emotional responses, and a slower return to baseline. When emotional vulnerability is combined with an invalidating environment, where emotions are dismissed, punished, or misunderstood, people often learn to suppress or distrust their internal experiences. Over time, this combination can make anger particularly volatile. Suppressed anger does not disappear. Instead, it often builds beneath the surface until it is triggered suddenly and intensely. Many people describe feeling calm one moment and flooded with anger the next, with little sense of control. This is not a failure of character. It is a predictable outcome of emotional vulnerability interacting with chronic invalidation and stress. Understanding this model helps reduce shame. Anger is not evidence that someone is dangerous, broken, or manipulative. It is evidence that their emotional system has learned to respond strongly in the face of perceived threat or pain. The Role of the Autonomic Nervous System To fully understand anger, it is essential to look beyond thoughts and behaviour and consider the nervous system. The autonomic nervous system regulates arousal and threat responses automatically, without conscious choice. It has two primary branches that are relevant here: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. When the sympathetic nervous system is activated, the body prepares for action. Heart rate increases, breathing becomes shallow, muscles tense, and attention narrows. This is often referred to as the fight or flight response. Anger is closely linked to this state. The body is mobilised to protect, confront, or defend. For many people who experience intense anger, this activation happens extremely quickly. The nervous system interprets a situation as threatening before the rational mind has time to evaluate it. Past experiences, particularly trauma or repeated invalidation, can sensitise the nervous system so that it responds to present day situations as though they are dangerous, even when the threat is emotional rather than physical. Once the sympathetic system is highly activated, access to reflective thinking is reduced. This is why reasoning, reassurance, or being told to calm down rarely helps in the moment. The body is already in survival mode. The parasympathetic nervous system, particularly the branch involved in social engagement and calming, helps bring the body back to baseline. Learning to activate this system intentionally is a key part of managing anger effectively. DBT skills are designed not only to change thoughts or behaviours, but to work directly with nervous system activation. Anger, Control, and the Illusion of Choice One of the most painful aspects of anger for many people is the belief that they should be able to control it through willpower alone. When anger feels uncontrollable, this belief often turns into shame and self criticism. From a DBT perspective, this expectation is unrealistic and unhelpful. Anger is not a deliberate choice. The initial surge of anger happens automatically, driven by the nervous system and shaped by past learning. Choice enters the picture later, in how a person responds to the emotion once it has arisen. This distinction is crucial. People may not have control over whether anger appears, but they can learn skills to influence how it unfolds and how they act in response. Recognising this distinction allows people to move away from self blame and towards skill development. The goal is not to eliminate anger, but to increase the window between feeling anger and acting on urges that may cause harm. Highlighted DBT Skill: Mindfulness of Current Emotion One of the most effective DBT skills for working with anger is Mindfulness of Current Emotion. This skill involves turning attention towards the emotion itself, rather than away from it, without judgement or suppression. For anger, this means noticing the physical sensations, thoughts, and urges that are present, while allowing the emotion to rise and fall naturally. When practiced consistently, this skill helps interrupt the automatic escalation cycle. Naming anger and observing it creates a small but meaningful pause. This pause can reduce physiological arousal and prevent secondary emotions such as shame or panic from layering on top of the initial anger. Mindfulness of current emotion also supports nervous system regulation. By staying present and grounded, the parasympathetic system is more likely to engage, allowing the body to settle over time. This does not mean anger disappears immediately. It means that anger is experienced as tolerable rather than overwhelming. This skill is particularly powerful when combined with validation. Acknowledging that anger makes sense given the situation reduces internal conflict and resistance. Paradoxically, accepting anger often allows it to pass more quickly. Learning to Work With Anger, Not Against It Anger becomes most destructive when people feel they must either act on it or get rid of it entirely. DBT offers a middle path. Anger can be acknowledged, understood, and responded to thoughtfully. Over time, this approach reduces fear of anger itself, which is often what drives impulsive reactions. Developing these skills takes practice and support. Anger patterns are rarely changed through insight alone. They change through repetition, feedback, and learning in a structured environment that prioritises safety and validation. DBT Anger Management Program Starting in April To support people who struggle with intense or reactive anger, our DBT Anger Management Program is commencing in April. This program is grounded in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and is designed for adults who want to better understand their anger, reduce emotional escalation, and respond more effectively in challenging situations. The program focuses on building skills in emotional regulation, distress tolerance, mindfulness, and interpersonal effectiveness, with a specific emphasis on anger and nervous system awareness. Participants are supported to understand their own anger patterns, identify vulnerability factors, and practice skills in a structured and compassionate group setting. Anger does not need to define your relationships or your sense of self. With the right framework and support, it can become an emotion you understand and manage, rather than fear or fight against.

For many people seeking therapy, this expectation becomes a quiet source of shame. When change does not arrive on cue, it can feel like a personal failure rather than a reflection of how human change actually occurs. Emotional regulation, behavioural change, and identity development do not operate according to the calendar. They develop through repetition, practice, and time. Understanding this can be relieving. It allows space for change to unfold in ways that are realistic, compassionate, and sustainable. The Myth of the Fresh Start Symbolic dates are appealing because they offer a sense of order and control. They suggest a clean break from the past and a chance to begin again without baggage. This idea is deeply embedded in cultural narratives about self improvement and success. Emotionally, however, our nervous systems do not reset at midnight. The same habits, emotional sensitivities, attachment patterns, and stress responses continue into the next day. When we expect sudden change, we often set ourselves up for disappointment. The gap between expectation and reality can reinforce self criticism, hopelessness, or avoidance. In therapy, many clients describe cycles of recommitment followed by collapse. They may tell themselves that this time will be different, only to feel defeated when familiar struggles return. Over time, this can erode confidence in the possibility of change itself. How Change Actually Happens Meaningful change tends to occur gradually and often invisibly at first. It is shaped by small, repeated actions rather than dramatic decisions. Emotional regulation develops when the nervous system has repeated experiences of safety, containment, and choice. Behavioural change strengthens through practice in real situations, including moments where things do not go as planned. Identity development grows when people begin to see themselves responding differently over time. These processes are cumulative. Each time you pause instead of reacting, name an emotion instead of suppressing it, or return to a skill after forgetting it, you are reinforcing new neural pathways. This work is rarely linear. Progress includes setbacks, plateaus, and periods of frustration. None of these mean that change is not happening. Time matters because the brain learns through repetition. New patterns require consistent reinforcement before they feel natural or reliable. This cannot be rushed by motivation alone, nor can it be scheduled neatly around symbolic dates. Emotional Regulation Is Built, Not Decided Emotional regulation is often misunderstood as a decision to feel differently. In reality, it is a capacity that develops through experience. For many clients, intense emotions have been present for years or decades. These emotional responses were often adaptive at the time they developed. They may have helped someone survive, cope, or remain connected. Because of this, emotional patterns tend to be deeply ingrained. Regulation emerges when people learn to notice emotions earlier, tolerate discomfort, and respond with skill. This learning happens through repeated exposure to emotions in manageable doses, supported by skills and therapeutic relationships. Expecting immediate emotional change can inadvertently reinforce the idea that emotions are problems to eliminate. A more helpful approach is to focus on how emotions are met, understood, and responded to over time. Behavioural Change Requires Practice in Context Behavioural change is similarly shaped by repetition. Insight alone is rarely enough. Knowing why a behaviour exists does not automatically make it easier to change. New behaviours need to be practised in the same environments where old patterns occur. This includes moments of stress, fatigue, or emotional vulnerability. It also includes moments where attempts at change do not go well. Each attempt provides information. Over time, this information helps refine responses and build confidence. When change is framed around calendar milestones, there is often little tolerance for imperfection. When change is framed as a practice, there is more room for learning and adjustment. Identity Develops Through Lived Experience Identity is not something that changes through intention alone. It develops through lived experience and accumulated evidence. People begin to see themselves differently after they have responded differently many times. For example, someone may begin to identify as more resilient after repeatedly surviving difficult moments without collapsing or acting against their values. This shift often happens quietly and retrospectively. Clients frequently report noticing change only when they look back and realise they handled something differently than they would have in the past. This kind of identity development does not align neatly with symbolic dates. It unfolds as a byproduct of sustained effort and patience. Skill Highlight: Mindfulness Non Judgementally One DBT skill that strongly supports this process is mindfulness non judgementally. This skill involves noticing thoughts, emotions, sensations, and urges without labelling them as good or bad, right or wrong, success or failure. Judgement often accelerates emotional intensity. When experiences are judged harshly, the nervous system moves quickly into threat responses such as shame, avoidance, or self attack. Non judgement creates space. It allows experiences to be observed rather than fought. Practising non judgement does not mean approving of harmful behaviours or ignoring the desire for change. It means accurately naming what is present without adding layers of criticism. For example, noticing “I am feeling overwhelmed and wanting to withdraw” rather than “I am weak for feeling this way.” Over time, this skill supports emotional regulation by reducing secondary emotions such as shame and anger at oneself. It also supports behavioural change by making it easier to return to skills after setbacks. Instead of viewing a lapse as proof of failure, it becomes information about what was difficult in that moment. A Client Vignette Consider the experience of a client who came to therapy feeling discouraged after many failed attempts at change. Each January, she committed to being calmer in relationships. By February, she felt ashamed that she was still reacting intensely to perceived rejection. In therapy, the focus shifted away from dates and resolutions. Instead, attention was given to noticing emotional responses as they arose. Using mindfulness non judgementally, she practised naming her reactions without criticism. When she felt the urge to send multiple messages or withdraw completely, she learned to pause and describe the urge rather than act immediately. Over several months, there were many moments where she still reacted in ways she disliked. However, there were also moments where she noticed earlier, paused briefly, or repaired more quickly. These moments did not feel significant at the time. Later, she reflected that she no longer experienced herself as out of control in the same way. This shift did not occur at the start of a year or after a particular milestone. It emerged gradually through repetition, support, and patience. Letting Go of the Calendar as a Measure of Progress When change is measured against the calendar, it can obscure real progress. Subtle shifts may be overlooked because they do not fit the narrative of a fresh start. Learning to notice progress in how you respond, recover, and relate to yourself can be more meaningful than any symbolic date. Therapy is not about becoming a new person overnight. It is about building capacity over time. Each moment of awareness, each return to a skill, and each act of self respect contributes to change, even when it does not feel dramatic. Meaningful change is rarely sudden. It is steady, uneven, and deeply human. When we release the expectation that change should follow the calendar, we create space for it to unfold in ways that are real and lasting.

Most of us want to change something about our lives — to feel calmer, relate differently, stop repeating old patterns, or simply get unstuck. Yet, even when the desire for change is strong, something inside resists. Clients often tell me, “I know what I should do, but I can’t seem to make myself do it.” That gap between intention and action is where DBT does its best work. DBT recognises that change is not just a decision; it’s a process that unfolds against the background of our biology, emotions, environment, and history. When we try to change, we’re not fighting laziness — we’re negotiating with our nervous system, habits, and fears. DBT is built on the dialectic of acceptance and change. Both are needed. Acceptance helps us see things as they are without judgement. Change gives us the tools to move forward effectively. Without acceptance, we stay stuck in resistance; without change, acceptance becomes resignation. The Science of Resistance From a psychological perspective, change threatens predictability. Our brains are wired to prefer the familiar, even when it’s painful. The amygdala; the brain’s alarm system interprets uncertainty as danger, triggering avoidance or over-control responses. For individuals with heightened emotional sensitivity, that threat response can feel overwhelming. In DBT, we frame this as part of the problem to be solved, not a personal flaw. Resistance becomes data. It tells us that part of the mind is trying to protect us from discomfort, rejection, or loss. Change, in this light, means learning to approach discomfort rather than eliminate it. “I Want to, But I Freeze” During one group session, Emma (not her real nam) shared that she felt “paralysed” every time she tried to set boundaries with her partner. She understood the skill intellectually but said, “When I open my mouth, I freeze. My heart races, my brain blanks out, and I end up giving in.” Instead of focusing on the boundary itself, we paused to notice what was happening in her body- the tightening chest, the urge to appease. Together, we practised mindfulness of current emotion and the TIPP skill (Temperature, Intense exercise, Paced breathing, Progressive relaxation). Within a few weeks, Emma learned that regulating her physiological arousal first made space for skillful action. This is what DBT means by building mastery through small steps. We do not demand instant transformation; we teach the body and mind to tolerate discomfort in manageable doses. The Role of Willingness One of the central concepts in DBT’s Reality Acceptance module is willingness- the capacity to open oneself to what is, and to do what works in the moment, even when it’s uncomfortable. Its opposite, wilfulness, sounds like resistance: “I don’t want to,” “I shouldn’t have to,” or “It won’t work anyway.” Wilfulness is a natural human reaction to pain. When life feels unfair, wilfulness tries to reclaim control. Yet, paradoxically, it keeps us stuck. Willingness, by contrast, invites movement. It doesn’t mean liking reality, agreeing with it, or giving up; it means choosing to participate fully in the present moment so that change becomes possible. In therapy, I sometimes invite clients to practise “turning the mind” consciously shifting from wilfulness to willingness. We pause, breathe, and ask: What would willingness look like right now? This small question often opens the door to action. Skill Spotlight: Willingness vs Wilfulness Here’s how to practise this skill at home: Notice resistance. Pay attention to moments when you feel yourself saying “no” to reality. It might appear as tension in your shoulders, self-critical thoughts, or avoidance behaviours. Pause and breathe. Take a slow, mindful breath. Unclench your hands or soften your posture — physical willingness supports emotional openness. Name the wilfulness. Silently acknowledge, “I’m feeling wilful right now.” Naming it reduces its power. Turn the mind. Intentionally choose willingness: “I am open to doing what works.” Act effectively. Take one small, value-aligned step, even if it’s uncomfortable. Over time, this practice helps clients move from avoidance to participation, from rigidity to flexibility. “I’m Scared It Won’t Work” Another client, Renee, struggled with hopelessness. After years of therapy, she feared nothing would change. Early in DBT, she often said, “What’s the point? I’ve tried everything.” In one session, we used the “Pros and Cons” skill — a DBT strategy for increasing motivation by writing out the short- and long-term consequences of acting on or resisting a behaviour. Together, we explored the pros and cons of avoiding therapy homework versus practising one new skill per week. Initially, the pros of avoidance were compelling: less anxiety, less effort. But the long-term cons — feeling stagnant, disconnected, and self-critical — resonated deeply. By visualising both paths, Renee recognised that staying still was also a form of suffering. Her willingness to experiment with small behavioural changes grew from that insight. Within months, she began journalling daily and practising mindfulness for three minutes each morning. Her mood improved, not because the work was easy, but because she was no longer at war with herself. Balancing Acceptance and Change At the heart of DBT is dialectical thinking- the idea that two seemingly opposite truths can both be valid. You can accept yourself fully and still want to change. You can acknowledge pain and choose to act effectively. This balance transforms black-and-white thinking into a more flexible, compassionate stance toward life. Clients often describe this as a relief. Instead of asking, “What’s wrong with me?” they begin asking, “What skill could help me here?” That shift alone is profound. Why Small Steps Matter Change rarely arrives in grand gestures. It shows up in the moment you pause instead of reacting, the time you validate yourself instead of criticising, or when you attend group despite wanting to cancel. Each act of willingness strengthens neural pathways associated with self-regulation and hope. In DBT, we celebrate these micro-changes because they reflect real, lived transformation. The goal isn’t perfection, it’s effectiveness: doing what works in the service of a life worth living. Moving Forward If you find yourself stuck between wanting change and fearing it, you’re not alone. Every client who has ever walked into a DBT session has felt that same ambivalence. The work begins with acknowledging both sides: the part of you that hopes and the part that hesitates. Start small. Practise willingness once a day. Try a skill even when you don’t feel ready. Change begins in those moments of gentle persistence. You don’t have to believe it will work; you only have to be willing to try ~ that is the heart of DBT.

Chain analysis is at the heart of DBT’s behavioural approach. It can be confronting, often emotional, and at times deeply challenging. Yet it is also one of the most illuminating exercises in therapy. When done thoughtfully and with support, it transforms moments of struggle into opportunities for insight, accountability, and growth. What Is a Chain Analysis? A chain analysis is a detailed examination of a specific behaviour that has caused distress or problems. It might be self-harm, substance use, an angry outburst, avoidance, or withdrawal. Rather than judging the behaviour, DBT invites curiosity: What happened before, during, and after this behaviour? The term “chain” refers to the sequence of links that connect an initial prompting event to the final behaviour. Each link represents a thought, feeling, physical sensation, or action that moved the person one step closer to acting on the behaviour. The process involves several steps: 1. Identifying the Target Behaviour – Naming the behaviour that caused suffering or went against one’s goals or values. 2. Describing the Prompting Event – Understanding what set the chain in motion. 3. Listing the Links in the Chain – Tracing every internal and external event, including thoughts, emotions, sensations, urges, and actions, that followed the prompting event. 4. Recognising Consequences – Looking at what happened after the behaviour: the short-term relief and the long-term costs. 5. Identifying Vulnerability Factors – Acknowledging what made the person more susceptible to reacting (for example, lack of sleep, hunger, conflict, medication changes, or stress). 6. Developing Solutions – Generating skills and strategies to break the chain in the future. This step-by-step analysis brings awareness to patterns that are often automatic or outside conscious awareness. Why Chain Analysis Matters In DBT, behaviour is never random. Every behaviour, no matter how confusing or painful, makes sense when understood in context. Chain analysis allows us to see that context clearly. It shifts the question from “What’s wrong with me?” to “What happened to me, and how did I respond?” Through this lens, behaviours that once felt shameful or self-destructive can be seen as understandable efforts to cope with unbearable emotional pain. This shift reduces self-criticism and opens the door to compassion and change. For therapists, chain analysis is not about blame but about understanding the function of the behaviour. For clients, it becomes a map: a way to track where things went off course and how to take a different path next time. How Chain Analysis Helps Identify Behavioural Patterns Over time, completing several chain analyses reveals recurring themes. You may begin to notice that certain emotions, like shame or fear of rejection, often appear just before a behaviour. You might see that particular situations, times of day, or relationships tend to activate intense feelings. For example: An individual might realise that self-harm tends to follow arguments with a partner. Another might notice that binge eating happens most often after long days without self-care or sleep. Someone else might see that avoiding therapy sessions comes after feelings of failure or hopelessness. Once these links are visible, they can be interrupted. By identifying “early warning signs,” clients learn when to apply DBT skills such as self-soothing, opposite action, or checking the facts before the behaviour spirals out of control. In this way, chain analysis is not just reflective; it is strategic. It provides the evidence base for what skills need to be practised and when. The Emotional Challenge of Doing Chain Analysis There is no denying that chain analysis can be difficult. It requires honesty and vulnerability. Many people feel reluctant at first, fearing that looking too closely at painful moments will make things worse. Yet the process is never about shame. It is about self-understanding. The therapist’s role is to guide the person gently, ensuring safety and validation at every step. The difficulty often lies in slowing down the memory enough to see all its parts: the fleeting thoughts, body sensations, and urges that felt overwhelming at the time. For people who have lived with trauma, shame, or chronic emotion dysregulation, this can feel emotionally charged. However, the hardness of chain analysis is also what makes it transformative. By facing the event with mindfulness and support, clients begin to remember differently, not as victims of chaos but as observers of their own patterns. This shift builds mastery and agency. Chain Analysis and Change: From Insight to Action Understanding is only half the work. The next step is change. Once the chain has been mapped, clients and therapists work together to create a solution analysis , a plan for what could be done differently in the future. This may include: Preventing vulnerability factors , such as improving sleep, nutrition, or stress management. Using mindfulness skills to notice the first emotional or physical signs of distress. Practising opposite action , doing the opposite of the urge that leads to trouble. Rehearsing new coping responses for high-risk situations. In this way, every behaviour becomes a learning opportunity. Each chain analysis provides real data about what works and what does not, refining the individual’s skill set over time. This process reflects DBT’s dialectical stance, balancing acceptance and change. Individuals learn to accept themselves as they are while also working towards the life they want to live. How Chain Analysis Builds Self-Compassion and Responsibility An unexpected benefit of chain analysis is how it nurtures both accountability and self-compassion. When we understand that our behaviour emerged from a chain of emotional, environmental, and cognitive links, we can hold ourselves responsible without shame. For many clients, this is a profound relief. Instead of labelling themselves as “ bad ” or “ broken ,” they begin to see that their actions make sense given their experiences. And if behaviours make sense, they can also be changed. This balance, compassion without excuse and accountability without blame, is the essence of DBT. A Skill for Life The longer individuals practise DBT, the more natural chain analysis becomes. Eventually, they begin to run through a “mini-chain” in their minds after difficult moments, asking: What just happened? How was I feeling? What did I tell myself? What could I do differently next time? This reflective capacity is the foundation of emotional intelligence and resilience. Over time, it empowers people to respond rather than react, to make choices aligned with their goals, and to live more effectively, even in the face of pain. Final Thoughts Chain analysis is not easy work. It demands courage, self-honesty, and patience. But it is also one of the most rewarding parts of DBT. Through this process, individuals gain a deep insight into their emotional world, discover the skills that help them stay on track, and build a sense of control over behaviours that once felt uncontrollable. Each time a chain analysis is completed, a small act of change takes place. Understanding replaces confusion. Self-compassion replaces shame. And step by step, link by link, people move closer to building a life worth living .

This dialectical dilemma describes what happens when strong, fast, and long-lasting emotions collide with a harsh inner critic. Instead of offering care, we tell ourselves our feelings are wrong or “too much.” Over time, this cycle drains self-worth and intensifies suffering. Emotional Vulnerability Emotional vulnerability refers to a heightened sensitivity to emotional cues, rapid reactivity, and slower return to baseline. Research shows that people with high vulnerability often have more active limbic systems and less efficient prefrontal regulation. This means emotions feel like they arrive louder and faster than they do for others. Examples of vulnerability in everyday life: Crying easily when disappointed. Feeling anxious for hours after a small social mishap. Reliving painful memories intensely. This is not weakness—it is a biological sensitivity often paired with histories of trauma or invalidation. Self-Invalidation Self-invalidation is the habit of dismissing or attacking our own internal experiences. It can sound like: “I’m overreacting.” “Other people cope better, I’m pathetic.” “I should just get over it.” Studies link self-invalidation to higher rates of self-harm and suicidal thinking. Rather than soothing distress, self-invalidation amplifies the original emotion, layering shame on top of pain. A Vignette: Sarah’s Cycle Sarah (not her real name) often described herself as “emotionally messy.” One afternoon she texted a friend who didn’t reply. Almost instantly she felt anxious and rejected. Instead of validating her hurt, Sarah told herself, “You’re pathetic for caring so much.” The more she criticised herself, the more distressed she became. Through DBT, Sarah learned that both sides of her experience could be valid: her sadness made sense, and her self-critical response also came from years of internalised invalidation. With practice, she learned to say, “Of course I feel hurt when I don’t hear back, anyone could. It doesn’t mean I’m unworthy.” How DBT Helps Break the Cycle DBT doesn’t aim to erase sensitivity. Instead, it teaches people to respond with validation and balance. Two skills are especially important here: Recovering from Self-Invalidation and Thinking Dialectically. Recovering from Self-Invalidation The DBT handout on Recovering from Invalidation reminds us that invalidation can sometimes be helpful (e.g., correcting factual mistakes), but it is often deeply painful when our inner or outer worlds are dismissed. Steps to practice: Check the facts. Ask: “Do my feelings make sense given the situation?” Even if they don’t fit the facts perfectly, feelings always have a cause. Drop judgmental self-talk. Replace “I’m overreacting” with “I’m doing the best I can with the skills I have.” Self-validate as you would a friend. If a friend felt hurt, you might say, “It makes sense you’re upset.” Offer the same compassion inward. Practice radical acceptance. Acknowledge that invalidation (past or present) has happened, and grieve the pain it caused Example : If you notice yourself thinking, “I shouldn’t be sad about this,” pause and try: “My sadness is real. It may not match the whole situation, but it makes sense given my history.” Thinking Dialectically Dialectics is at the heart of DBT: the idea that two seemingly opposite things can both be true. Key principles include: Look for the kernel of truth in the other side. Replace “either/or” with “both/and.” Validate both sides: “I don’t like this reality, and I can accept it. Embrace change as the only constant. Everyday practice examples: When you catch yourself saying, “I’ll never cope,” reframe as: “This is really hard, and I can take one step at a time.” If you’re arguing with a loved one, practice finding the piece of truth in their perspective; even if you don’t agree with all of it. Notice when you swing to extremes (“always,” “never”) and soften it to “sometimes.” Why It Matters Emotional vulnerability, when paired with self-validation and dialectical thinking, can become a strength. Sensitivity allows for deep empathy and creativity. DBT skills transform the vulnerability–invalidation loop into a balanced pathway of acceptance and skilful change. At Wise-Mind DBT Brisbane, we specialise in teaching these skills. If you recognise yourself in this cycle, know that your feelings make sense—and with practice, you can learn to respond to them differently.

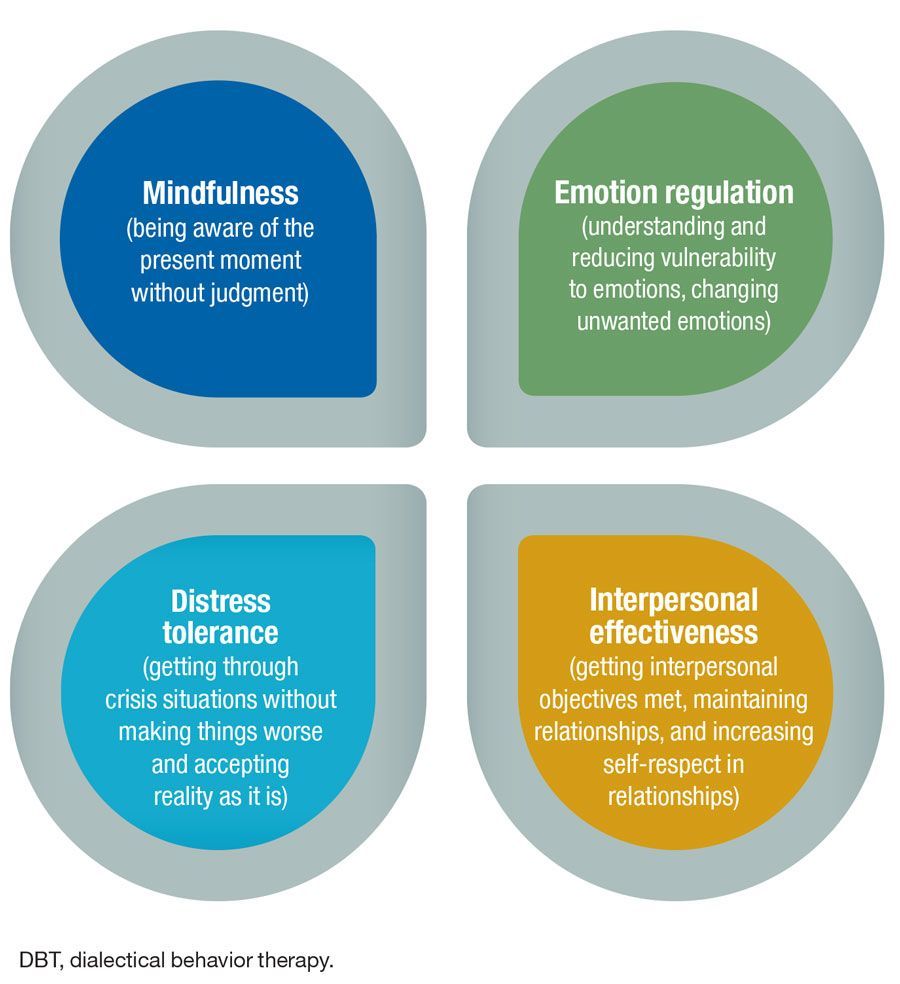

This structured program is facilitated by experienced DBT therapists and includes weekly sessions that are evidence-based, trauma-informed, and designed to foster real-world skill application. Below, we outline what participants can expect and why short-term DBT skills training is both effective and accessible. How the Program Works Over the course of 13 weeks, participants will engage in weekly 2-hour group sessions covering the four key DBT modules: Weeks 1–3: Mindfulness Introduction to DBT and the rationale behind mindfulness Learning to observe, describe, and participate without judgment Developing present-moment awareness and reducing automatic reactivity Weeks 4–7: Emotion Regulation Understanding the function of emotions and identifying emotional patterns Learning how to decrease vulnerability to negative emotions Applying strategies like opposite action and problem solving Weeks 8–10: Distress Tolerance Developing practical crisis survival skills for managing emotional pain Introducing techniques such as TIPP (Temperature, Intense Exercise, Paced Breathing, Paired Muscle Relaxation) Cultivating radical acceptance for situations that cannot be changed Weeks 11–13: Interpersonal Effectiveness Learning how to ask for needs, say no, and navigate difficult conversations Practising assertiveness while maintaining self-respect and relationships Building skills for boundary-setting and conflict resolution Each session includes: A mindfulness practice Review of the previous week’s homework Teaching and discussion of new skills In-session exercises to promote skill acquisition Why 13 Weeks? Evidence for Short-Term DBT You might be wondering: Is 13 weeks long enough to make a difference? The research says yes. A randomised controlled trial by Soler et al. (2009) compared DBT skills training (DBT-ST) delivered over 13 weeks with standard group therapy for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The study found that DBT-ST was significantly more effective in improving mood symptoms (such as depression, anxiety, and anger), emotional instability, and general psychiatric distress. Importantly, dropout rates were also much lower in the DBT-ST group—just 34.5% compared to 63.4% in the standard therapy group. This suggests that even a short-term DBT program can be both engaging and clinically impactful, particularly when it focuses on core skills training with an experienced facilitator team. “Three-months weekly DBT-ST proved useful. This therapy was associated with greater clinical improvements and lower dropout rates than standard group therapy… and provides the additional advantage that it is cost-effective” (Soler et al., 2009, p. 354). Additional Features of the Program Homework : Between-session practice is essential. Each participant receives tailored homework to apply the skills in real-life scenarios. Group Cohesion : The small group setting (6-8 participants) encourages safety, support, and shared learning. Trauma-Informed Approach : We recognise the impact of complex trauma and work from a stance of compassion, validation, and non-judgement. Accessibility : This 13-week program offers an evidence-based alternative for those unable to commit to a full year of DBT. Is This Group Right for You? This program is ideal for individuals who: Struggle with emotional sensitivity, reactivity, or intense mood shifts Want to build better relationships and assert boundaries Are seeking skills to manage urges, distress, or impulsive behaviours May not require or cannot access year-long DBT but are seeking meaningful change To express interest or register for the August 23rd group, please get in touch via {{content_library.global.email.email}} or phone us on {{content_library.864586003.phone.business phone}} directly. We’d love to support you in building a life worth living—one skill at a time. References Soler, J., Pascual, J. C., Tiana, T., Cebrià, A., Barrachina, J., Campins, M. J., Gich, I., Álvarez, E., & Pérez, V. (2009). Dialectical behaviour therapy skills training compared to standard group therapy in borderline personality disorder: A 3-month randomised controlled clinical trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(5), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.013

At Wise-Mind DBT Brisbane, we’re often asked: “Do I really need a full year of DBT to feel better?” While standard DBT programs traditionally span 12 months, new evidence shows that shorter, skills-based DBT groups—such as our 12-week format—are highly effective for improving emotional regulation, reducing psychological distress, and enhancing wellbeing. What the Evidence Shows A recent systematic review by Hernandez-Bustamante et al. (2024) examined 18 randomised controlled trials and confirmed that DBT, whether delivered in full or abbreviated formats, leads to consistent improvements in emotional regulation, impulsivity, and symptoms of depression. Notably, even short-term DBT programs significantly reduced self-harming behaviours and suicidal ideation, with benefits often persisting for up to two years after treatment. The authors emphasised that DBT skills training, as delivered in group formats—was particularly effective in reducing shame-based behaviours such as self-harm. Similarly, Kujovic et al. (2024) compared 8-week and 12-week inpatient DBT programs and found no significant difference in treatment outcomes between the two durations. Both groups showed substantial reductions in borderline symptom severity and depressive symptoms, with large effect sizes across both domains. This reinforces the idea that a well-structured 12-week DBT group is not only effective—it is efficient. Why Emotion Regulation Matters (and How DBT Helps) Emotion regulation is more than simply "controlling your feelings." It refers to the ability to understand, label, and modulate emotional experiences in a way that supports—rather than disrupts—daily functioning and wellbeing. For individuals with high emotional sensitivity—particularly those diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder or Complex PTSD emotions can feel overwhelming, unpredictable, and deeply shame-laden. When emotions become too intense or prolonged, many people turn to impulsive or avoidant behaviours such as self-harm, substance use, or conflictual relationship patterns. The Emotion Regulation module in DBT is specifically designed to address this. In group sessions, participants learn to: Recognise and track emotional patterns Reduce emotional vulnerability by caring for physical and psychological wellbeing Apply strategies to shift the intensity of unwanted emotions Increase experiences of positive emotions Replace ineffective coping with more skilful responses Both Hernandez-Bustamante et al. (2024) and Kujovic et al. (2024) highlight that improvements in emotion regulation are a key mechanism of change in DBT. These skills not only reduce risk but also empower clients to respond more flexibly and thoughtfully in the face of stress. The Four Pillars of DBT Skills Training At Wise-Mind DBT Brisbane, our 12-week group follows the core DBT curriculum, which is structured around four evidence-based modules. These work together to help individuals build a more resilient, values-driven life: 1. Mindfulness Mindfulness is the foundation of DBT. It teaches participants how to observe and describe thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations in the present moment—without judgment. This skill increases awareness and decreases reactivity, allowing for more thoughtful and compassionate responses to distressing experiences. 2. Distress Tolerance Life is full of painful moments that cannot be immediately changed. Distress Tolerance skills help individuals manage crises without making the situation worse. This module teaches short-term strategies such as distraction, self-soothing, and radical acceptance, which are especially helpful in early recovery or during acute stress. 3. Emotion Regulation Building on mindfulness, the Emotion Regulation module teaches participants how to understand and influence their emotional experience. By learning how to reduce vulnerability to emotion mind and increase positive experiences, individuals are better equipped to navigate emotional ups and downs with stability and confidence. 4. Interpersonal Effectiveness Many individuals who enter DBT report difficulties in relationships—whether it’s asking for what they need, setting boundaries, or managing conflict. This module teaches practical skills to improve communication, strengthen connections, and maintain self-respect. These tools reduce interpersonal chaos and foster more balanced, respectful relationships. Ready to Join Our Next Group? Our next 12-week DBT Skills Group begins Saturday, 23 August . Whether you are looking to build emotional resilience, reduce distress, or develop healthier relationship patterns, this program offers a structured, skills-based pathway grounded in research and delivered with compassion. References Hernandez-Bustamante, M., Cjuno, J., Hernández, R. M., & Ponce-Meza, J. C. (2024). Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy in the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 19(1), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijps.v19i1.14347 Kujovic, M., Benz, D., Riesbeck, M., Mollamehmetoglu, D., Becker-Sadzio, J., Margittai, Z., Bahr, C., & Meisenzahl, E. (2024). Comparison of 8-vs-12 weeks, adapted dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) for borderline personality disorder in routine psychiatric inpatient treatment—A naturalistic study. Scientific Reports, 14, Article 11264. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-61795-9 Spots are limited. Click below to register your interest and take the first step towards emotional balance and meaningful change.

What is Catastrophising? Catastrophising is a type of cognitive distortion where the mind leaps to the worst possible outcome—regardless of how unlikely it might be. It can involve: - Assuming a situation is far worse than it really is, - Predicting total failure or devastation based on a small setback, - Reacting as though disaster is certain, even in the absence of evidence. For example: “I made a mistake at work. My boss is going to fire me. I’ll never get another job. I’ll end up alone and homeless.” In this thinking pattern, the emotional response is not to the situation itself, but to the imagined catastrophe. The brain responds to perceived threat—whether real or imagined—as if it’s actually happening. This can trigger a cascade of anxiety, shame, panic, and impulsive urges to fix or escape the situation. Why is Catastrophising So Common in BPD? People with BPD often experience intense sensitivity to perceived abandonment and rejection. This can lead the brain to treat any social rupture—no matter how small—as a threat to survival. If you grew up in an invalidating or unpredictable environment, it makes sense that your nervous system might now be wired to anticipate the worst. In this way, catastrophising becomes a (very painful) attempt at emotional self-protection. By preparing for rejection, failure, or abandonment, it can feel like you're trying to shield yourself from hurt. Unfortunately, this strategy tends to backfire, reinforcing emotional distress and leading to behaviours that may push others away—just as feared. The Impact of Catastrophising Catastrophising in BPD often leads to: - Intense emotional dysregulation – fear, anger, shame, despair. - Impulsive behaviours – self-harm, substance use, over-apologising, or cutting off relationships. - Difficulties in relationships – as others struggle to respond to disproportionate emotional reactions. - Self-fulfilling prophecies – where feared outcomes become more likely due to reactive behaviour. These effects can reinforce a painful cycle of suffering and disconnection, making everyday life feel unpredictable and exhausting. DBT Skills That Can Help Dialectical Behaviour Therapy offers a range of tools that specifically address catastrophising. Here are some that clients often find helpful: Check the Facts This skill invites you to slow down and assess whether your emotional response fits the actual facts of the situation. Ask: - What is the actual situation? - What am I telling myself about it? - Are there other possible explanations? - What is the most likely, and not the worst, outcome? By grounding your thoughts in observable facts, you begin to weaken the hold of catastrophic thinking. Mindfulness of Current Emotion Instead of trying to escape the overwhelming feelings catastrophising brings, this skill teaches you to *observe*, *name*, and *ride out* the emotion like a wave. This builds tolerance and reduces the need to act impulsively in response to fear or anxiety. Try saying: “This is fear. Fear is here right now. I can notice it without needing to fix everything.” When we catastrophise, our minds rush to imagined futures filled with rejection, failure, or disaster. In response, strong emotions like fear, panic, shame, or anger can flood our nervous systems. These emotions feel overwhelming and dangerous—something to *fix*, *escape*, or *avoid*. But in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy, we take a radically different approach: we learn to **stay with the emotion**, *as it is*, without needing to change it immediately. **Mindfulness of Current Emotion** is a core Emotion Regulation skill that teaches you to fully experience your emotions—without suppressing, judging, or acting impulsively on them. By turning toward the emotion with awareness, you build emotional tolerance and reduce the urgency to act in unhelpful or self-defeating ways. The Steps of Mindfulness of Current Emotion: 1. Notice the emotion in your body Where do you feel it? Is it tightness in your chest? A pit in your stomach? Heat in your face? Describe the sensations with curiosity, not judgment. 2. Name the emotion Give the emotion a label—fear, shame, sadness, anger. Naming an emotion activates the prefrontal cortex and helps regulate the intensity of what you're feeling. 3. Allow the emotion to be there Don’t push it away or try to “fix” it. Emotions are like waves: they rise, crest, and pass. Trust that this feeling, like all feelings, is temporary. 4. Avoid impulsive action The urge to *do something*—text, lash out, self-harm, or isolate is often a response to discomfort, not necessity. Pause. Breathe. You can choose not to act on the emotion. 5. Remember: You are not your emotion Say to yourself, *“This is just an emotion. I can feel it, and I can let it pass.”* This creates space between you and the experience, building the capacity to respond, rather than react. Why This Skill Matters In BPD, emotional experiences can feel all consuming, as if they define the self: *“I feel worthless, so I must be worthless.”* By observing emotions mindfully, you begin to decouple your identity from your emotional state. You learn that you can feel intense distress without being destroyed by it, and without needing to make decisions based on that distress. Practising Mindfulness of Current Emotion helps to interrupt the cycle of catastrophising by: - Grounding you in the present moment (instead of feared future outcomes), - Helping you tolerate discomfort without acting impulsively, - Reducing avoidance of painful emotions, which often prolongs suffering. This skill doesn’t make emotions disappear—but it does reduce their control over your behaviour and your sense of self. Like all DBT skills, this takes practice—but over time, it builds emotional resilience, clarity, and a growing sense of self-trust.

How Do Eating Disorders Start? Many individuals with BPD and eating disorders describe similar patterns of emotional distress that lead to compulsive eating behaviours. The onset of binge eating disorder often stems from: Restrictive Dieting: Cutting calories too aggressively can trigger intense cravings, leading to binge eating. Emotional Coping: Many people use food as a way to manage stress, trauma, or overwhelming emotions. Early Experiences: Childhood trauma, bullying, or growing up in a toxic home environment can contribute to food becoming a source of comfort. Guilt and Shame Cycle: The cycle of binge eating, followed by guilt and further restriction, reinforces unhealthy eating habits. These patterns can quickly spiral into an exhausting roller coaster of highs and lows, making recovery challenging without the right support. The Overlapping Traits Between BPD and Eating Disorders BPD is characterized by emotional dysregulation, unstable relationships, and an intense fear of abandonment—factors that often intersect with eating disorders. Here’s why they frequently co-exist: Emotional Dysregulation People with BPD experience extreme mood swings, often using food as a coping mechanism for overwhelming emotions. Impulsivity Impulsive behaviours, such as binge eating, purging, or restrictive eating, are common among individuals with BPD. Distorted Self-Image Low self-esteem and an unstable sense of self contribute to both BPD and eating disorders, often leading to extreme behaviours around food. Fear of Abandonment People with BPD often seek external validation, sometimes through controlling their weight and appearance. Trauma History Both conditions are linked to past experiences of abuse, neglect, or other traumatic events, reinforcing unhealthy coping mechanisms. Recognizing these overlapping traits can be the first step toward seeking appropriate treatment. The Feelings During and After Binge Eating Binge eating often provides temporary relief from emotional distress, but it quickly leads to guilt, shame, and exhaustion. The emotional process typically follows this pattern: 1. Before the Binge: Overwhelming cravings, often triggered by stress, sadness, or boredom. 2. During the Binge: A temporary escape, with feelings of excitement or comfort. 3. After the Binge: Intense shame, self-loathing, and sometimes further restriction or purging. 4. The Cycle Continues: These behaviours reinforce a cycle that can feel impossible to break. Many individuals with BPD and binge eating disorder report feeling powerless against their urges, making professional treatment crucial for recovery. The Path to Stopping the Cycle: Effective Treatment Approaches When BPD and an eating disorder co-exist, a holistic and integrative treatment approach is essential. Here are some of the most effective methods: Emotion Regulation Skills – Manage triggers & reduce emotional eating PLEASE – Take care of your Physical health, Lifestyle balance, Eating habits, Avoid mood-altering substances, Sleep, and Exercise to stabilise emotions. Opposite Action – If you feel the urge to binge out of sadness, do the opposite (e.g., go for a walk, call a friend). Check the Facts – Ask yourself: Am I really hungry, or am I trying to soothe an emotion? Distress Tolerance Skills – Cope without food as an escape TIPP – Use Temperature (cold splash), Intense exercise, Paced breathing, and Paired muscle relaxation to regulate urges. Urge Surfing – Cravings come in waves. Instead of acting on them, observe them like a passing tide. ACCEPTS – Distract yourself with Activities, Contributing, Comparisons, Emotions, Pushing away, Thoughts, and Sensations** instead of binging. Distress Tolerance Skills – Become aware of eating patterns Mindful Eating – Slow down, chew thoroughly, and truly experience each bite without distractions. Non-Judgmental Stance – Avoid self-shame. Instead of “I failed,” say, “I had a binge episode, and I can learn from this.” Radical Acceptance – Accept your emotions and experiences as they are, without resistance or self-criticism. Interpersonal Effectiveness – Set boundaries & seek support DEAR MAN – Communicate your needs assertively (e.g., asking for support, saying no to food pushers). FAST – Maintain self-respect when dealing with food-related guilt or judgment from others. Recovery is possible! ~ Using DBT skills can help you break free from the cycle of binge eating and build a healthier relationship with food. FAQs ❓ 1. Can BPD cause an eating disorder? While BPD doesn’t directly cause eating disorders, its symptoms—such as impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and trauma history—often contribute to disordered eating behaviours. ❓ 2. Why do people with BPD struggle with food? Food is often used as a way to cope with intense emotions, self-worth struggles, and a fear of abandonment—common traits of BPD. ❓ 3. What is the best therapy for BPD and eating disorders? Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and RO-DBT are highly effective for both conditions, as it helps with emotional regulation, impulsivity, and mindfulness. ❓ 4. How can I stop binge eating if I have BPD? Developing emotional regulation skills, using distress tolerance techniques, and seeking therapy can help manage binge eating urges. ❓ 5. Can someone recover from both BPD and an eating disorder? Yes! With the right combination of therapy, support, and self-awareness, individuals can recover and build a healthier relationship with food and emotions.

The Deep Need for Safety - Understanding, Healing, and Finding Inner Peace Being safe, both mentally and physically, greatly impacts how we live. When we feel unsafe, our minds and bodies react with stress, anxiety, and survival-driven behaviours. But what happens when our lives are consumed by constant fear and uncertainty? It becomes a curse that robs us of joy, preventing us from embracing life’s beautiful moments. If you struggle with these feelings, ask yourself: What makes me feel this way? How can I break free when fear feels like an unshakable part of my life? And what steps can I take to cultivate a lasting sense of safety? Why Safety Matters Feeling safe isn’t just about avoiding physical danger, mental and emotional safety are equally important. Safety is the foundation of human well-being and performance. When we feel safe, our bodies enter a state of relaxation and recovery, allowing us to heal, build resilience, and thrive. On the other hand, chronic feelings of unsafety trigger stress responses, affecting our mental, emotional, and physical health. Consider how new-born babies flourish when nurtured in a stable, loving environment. They grow not only physically but also emotionally and cognitively. In contrast, individuals raised in chaotic or abusive environments often struggle with chronic anxiety, trust issues, and even long-term physical health problems. Their bodies and minds become wired for hypervigilance rather than growth. And if you were raised in a chaotic or abusive environment, I want to tell you: You are not alone, and this is not the end of your story. Ending your life is not the solution. You are not your enemy, be kind to yourself. It’s not your fault. Life is unpredictable, and we are all just human. Unresolved trauma and unacknowledged pain can leave individuals feeling isolated, burdened, and disconnected from a sense of normalcy. When those who should provide protection fail to do so, it can create lasting wounds. Breaking free from these cycles requires seeking support, acknowledging past pain, and working toward healing. The Impact of Feeling Unsafe on the Mind and Body When we don’t feel safe, our nervous system shifts into survival mode. This activates the fight-or-flight response, flooding our bodies with stress hormones. Over time, chronic stress can cause severe mental and physical wear and tear, leading to issues such as: Anxiety and depression Difficulty forming or maintaining relationships Chronic physical illnesses Self-destructive behaviours as a coping mechanism One of the most damaging effects of chronic stress is the feeling of being trapped. Whether it’s being trapped in an unhealthy environment, toxic relationships, financial instability, or even our own negative thoughts, the sensation of having no control can fuel anger, frustration, and destructive actions. Harmful Coping Mechanisms and Breaking Free When we feel unsafe, we instinctively seek ways to regain control. Unfortunately, many of these coping strategies can be harmful in the long run. Some common responses include: Substances, gambling, food, or even social media can become temporary escapes from feelings of fear and insecurity. DBT Skills to Cope: Distress Tolerance (ACCEPTS & Self-Soothing): Engage in healthy distractions, such as listening to music, going for a walk, or practising deep breathing, to reduce urges. Radical Acceptance: Instead of avoiding pain through addiction, acknowledge reality as it is and work towards healthier coping mechanisms. Mindfulness: Stay present and observe cravings without acting on them, recognizing that they come and go like waves. DBT Skills to Cope: Interpersonal Effectiveness (DEAR MAN, GIVE, FAST): Learn to assert your needs without resorting to control or manipulation. Healthy relationships are built on respect and balance. Emotion Regulation (Opposite Action): If the urge to control arises from fear, practice the opposite by letting go in small, manageable ways and observing the outcome. Checking the Facts: Challenge distorted thoughts that make you feel the need for excessive control. Ask yourself, “Is this truly a threat?” DBT Skills to Cope: Self-Validation: Practice recognizing your feelings and experiences as valid, even if others don’t acknowledge them. Building Mastery: Engage in activities that give you a sense of competence and accomplishment, such as hobbies, learning, or small daily achievements. Wise Mind & Radical Acceptance: Balance logic and emotions when evaluating self-worth. Accept imperfections as part of being human rather than as failures. By using these DBT skills, we can develop healthier coping mechanisms and create a genuine sense of safety, one that isn’t dependent on harmful behaviours or external validation. Building a Lasting Sense of Safety True safety comes from within. It’s about creating an internal environment where we feel secure, resilient, and at peace, regardless of external circumstances. Here’s how we can foster genuine safety: Emotional Vulnerability Real human connection is built on trust and vulnerability. While society often discourages vulnerability, it is crucial for healing. Suppressing emotions, especially anger, only fuels more stress and disconnection. Learning to express emotions in healthy ways can reduce anxiety and create deeper relationships. Dynamic Healing Rather than just “managing” stress, dynamic healing focuses on shifting our nervous system from a constant threat state to one of safety. This involves: Mindfulness and grounding techniques to bring awareness to the present moment Therapy and self-reflection to address past trauma and negative thought patterns Breathwork and relaxation practices to regulate stress responses DBT Therapy and Skills Dialectical Behaviour Therapy is an evidence-based approach that can be incredibly effective in helping individuals feel safe and in control of their emotions. DBT skills such as distress tolerance, emotion regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and mindfulness help create long-term emotional stability. However, it’s important to note that progress with DBT is not an overnight success, it often takes months or even a year to see significant change. But the effort is worth it, as it leads to a deep and lasting sense of inner safety. Without committing to the process, you may constantly battle feelings of unsafety, missing out on the beauty and wonder that life has to offer. Creating Cues of Safety Our nervous system constantly scans for signs of danger or safety. By surrounding ourselves with positive environments, supportive relationships, and healthy routines, we can reinforce cues of safety and rewire our responses to stress. The Power of Positive Thinking One of the most important tools in creating a lasting sense of safety is the power of positive thinking. Thinking positively can help shift your mindset, making it easier to focus on what’s going well in your life rather than what’s wrong. Taking a moment each day to say something good about yourself, whether it's acknowledging your efforts, celebrating your achievements, or simply affirming your worth, can have a profound impact on your mental and emotional health. By regularly engaging in positive self-talk, you not only cultivate a sense of inner peace and safety, but you also rewire your brain to recognise and appreciate the good in your life. This simple yet powerful practice is key to building resilience, reducing anxiety, and ultimately healing from the inside out. When Feeling Unsafe Comes from Trauma or Life Circumstances Feeling unsafe may stem from a variety of sources, childhood trauma, toxic relationships, financial instability, or even personal fears. In these situations, it’s important to take a step back, breathe, and assess what you can do to resolve the issue. If you can solve it, take practical steps toward healing or improvement. If it feels overwhelming or beyond your control, don’t make the situation worse by allowing it to consume you. Instead, seek help. Reaching out to a trusted person or professional can provide you with the support and guidance you need to regain a sense of safety and peace. Final Thoughts Feeling safe is more than just avoiding danger, it’s about fostering a sense of internal peace and resilience. When we prioritize healing, embrace emotional vulnerability, and reframe our responses to stress, we create a life where we can truly thrive. The path to safety isn’t about control or avoidance, it’s about understanding, growth, and connection. By taking intentional steps and utilizing tools like DBT and positive thinking, we can move from merely surviving to truly living. Don’t let the fear of unsafety hold you back, life is full of beauty, connection, and joy, and you deserve to experience it all. FAQs 1. What does it mean to feel safe, and why is it so important? Feeling safe means experiencing a sense of security, physically, emotionally, and psychologically. It is essential for overall well-being, as it allows us to relax, heal, and function effectively. 2. How does chronic stress from feeling unsafe affect mental health? Chronic stress triggers anxiety, depression, and even physical illnesses by keeping the body in a constant state of fight-or-flight. Over time, this can lead to burnout and difficulty maintaining healthy relationships. 3. What are some common but unhealthy ways people try to feel safe? Many people turn to controlling behaviours, or perfectionism as coping mechanisms. While these strategies may offer temporary relief, they often lead to deeper issues in the long run. 4. How can I create a lasting sense of safety within myself? True safety comes from within and involves healing past trauma, practicing mindfulness, surrounding yourself with positive relationships, and using tools like DBT and self-affirmation to build resilience. 5. Can therapy help with feelings of unsafety? Yes, therapy, especially approaches like DBT, can help individuals regulate their emotions, reframe negative thought patterns, and build skills to feel safer and more in control of their lives.